I’m currently doing some reading in Legenda Aurea, the Dominican Jacobus de

Voragine’s great compendium of saints’ legends and other liturgical feasts,

designed to be a reference book for homilists. Jacobus compiled these stories

in the 1260s and relied on a wide range of Christian authors, often citing

contradicting views on certain matters as a summary of the views held by

previous authors. Legenda Aurea is

first and foremost a conservative compilation, since it contains only five

saints from Jacobus’ own time or the preceding century. Four of these modern

saints are connected with the vogue of mendicant sanctity that dominated the

religious sentiments of the Latin Mediterranean in the thirteenth century.

These are the mendicant founders Francis (d.1226) and Dominic (d.1221), the

Dominican friar and martyr Peter of Verona (d.1252) and the Franciscan tertiary

Elizabeth of Hungary (d.1231). The last of the modern saints is Thomas Becket

(d.1170) whose martyrdom in Canterbury cathedral Jacobus erroneously dates to

1174, the year after his canonization by Pope Alexander III.

This incorrect date suggests that although Jacobus was extremely well-read and

could draw references from a long and impressive list of sources, his knowledge

of English material was quite sparse. Jacobus’ lack of familiarity with English

hagiography becomes all the more apparent when you compare his original work

with the adaptations from thirteenth- and fourteenth-century England such as

the Gilte Legende, the South English Legendary and the Nova Legenda Anglie. Considering that

Jacobus probably envisioned only a relatively local circulation of his work,

his lack of English material is neither surprising nor something that merits rebuke,

but it does result in the occasional misinformation, such as the year of Becket’s

death.

Another piece of information is an interesting anecdote appended to his chapter

on St John the Apostle. Jacobus writes (in William Granger Ryan’s American translation):

Saint Edmund [of East Anglia], king of

England, never refused anyone who asked a favor in the name of Saint John the

Evangelist. Thus it happened one day when the royal chamberlain was absent that

a pilgrim importuned the king in the saint’s name for an alms [sic]. The king,

having nothing else at hand, gave him the precious ring from his finger. Some

time later an English soldier on overseas duty received the ring from the same

pilgrim, to be restored to the king with the following message: “He for whose

love you gave this ring sends it back to you.” Hence it was obvious that Saint

John had appeared to him in the guise of a pilgrim.

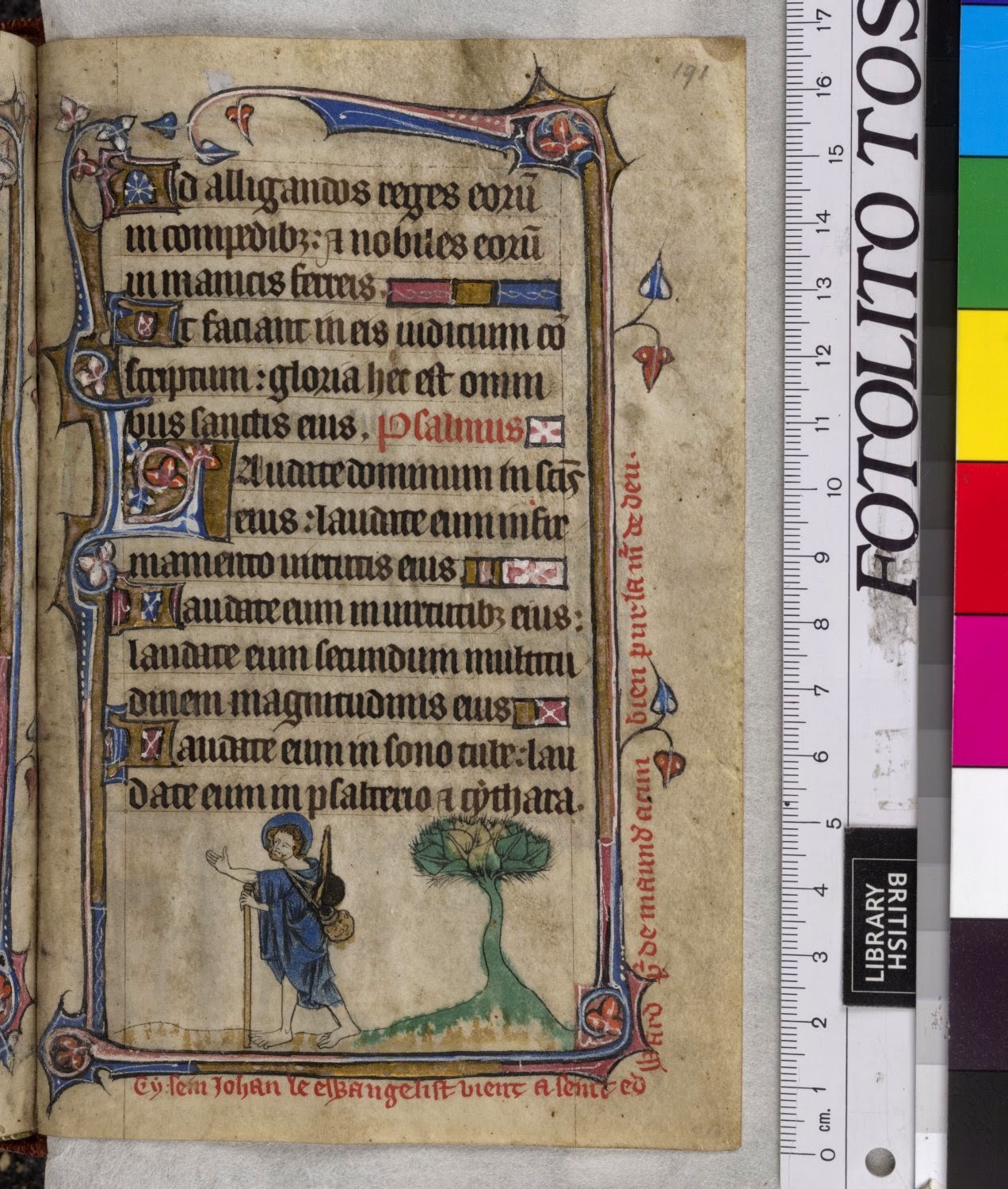

'Cy seynt Edward dona un anel a Iohan le ewangelist'

Courtesy of British Library

'Cy sein Johan le ewangelist vient a seint edward p[ur] demaund[er] acun bien pur lam[ur] de deu'

Courtesy of British Library

This anecdote is significant for several

reasons. First of all because it shows an interesting confluence of two of

high-medieval England’s most important saints: Edmund of East Anglia and Edward

the Confessor. The story of the king giving his ring to Saint John in disguise

belongs to the legend of Edward the Confessor and is perhaps one of the most

famous miracles from his hagiographies. It first appears in Aelred of Rievaulx’s

Vita Sancti Edwardi Regis, a work

written for the translation of Edward’s body in 1163, and which was

commissioned by Lawrence, abbot of Westminster. The ring became Edward’s main

attribute and remained so throughout the Middle Ages, as seen below from a

calendar page from the early 1400s.

Edward the Confessor holding his ring, oddly placed at March 18

Harley 2332, Almanac with astrological miscellany, England, 15th century (before 1412)

Courtesy of British Library

Jacobus’ attribution of this episode to the

legend of St Edmund is also significant because it allows us a glimpse of the

close relationship between those cults from the twelfth century onwards. Edmund

had been venerated as a saint since the late ninth century, and his cult centre

had been at Bury St Edmunds from the start. In the second half of the eleventh century

and onwards, the cult of St Edmund experienced an increased literary output of

hagiographical and liturgical material. A new, proper, liturgical office was composed between 1065 and 1087, and Herman the Archdeacon wrote De Miracula Sancti Edmundi c.1100. In the literature of Bury’s

long twelfth century, King Edward the Confessor – universally respected in

English history – was invoked as one of Edmund’s devotees, and as a just king

who granted the abbey many valuable charters. The generosity of Edward was a

recurring feature, appearing both in Herman’s De Miracula and Jocelin’s late-twelfth-century Chronicle of the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds.

Edward the Confessor was not canonised until 1161 and his cult was a product of

Westminster Abbey and the political interests of King Henry II. Edward’s cult

had a brief but intense first period of popularity which rapidly diminished at

the explosive growth of the cult of Thomas Becket in the 1170s. Becket’s cult

did not affect the cult of Edmund in the same way, much thanks to Bury being a

thriving literary centre, and brief anecdotes in late-twelfth-century

historiographies – such as Benedict of Peterborough’s Gesta Henrici II and Ralph Coggeshall’s Chronicon Anglicanum – suggests that Edmund enjoyed a much wider

and more stable veneration than did Edward.

Martyrdom of St Edmund

Courtesy of British Library

From the thirteenth century onwards, the two

royal saints began to appear together in both art and literature. We don’t know

which is the earliest example of this. Edward and Edmund – along with two

others – are both listed among England’s peaceable kings in the anonymous Anglo-Norman

Le Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei

from the 1240s, and in the late 1300s William Langland states in Piers Plowman that Edmund and Edward

were both followed by the personification of Charity. To name some of the

examples of these two appearing together in art, we have a glass cycle in

Amiens from c.1280, and perhaps the most famous instance of them all, the

Wilton Diptych where they appear together with John the Baptist as patron for

the young Richard II.

The Wilton Diptych

Edmund and Edward both displaying their most well-known attributes

Courtesy of Wikimedia

In all these instances mentioned above the

pairing of Edmund of Edward have been done deliberately, while in Jacobus’ Legenda Aurea the two saints have

blended together by mistake. The interesting question is whether this mistake

was owing to Jacobus’ own faulty memory, having heard the story from one of the

many English pilgrims in Italy and then confused the characters, or whether the

story was transmitted to Jacobus in the way he recorded it. In any case, the

faulty attribution of the miracle of the ring to Edmund of East Anglia,

suggests that by the latter half of the thirteenth century, the two royal

patrons of England may already have begun to be paired together, not only in

art and literature but also in the common imagination.

Literature

Anonymous, Le Estoire de Seint Aedward le

Rei, translated by Thelma Fenster and Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, ACMRS Press,

2008

Aelred of Rievaulx, The Life of Saint

Edward, King and Confessor, translated by Jane Patricia Freeland and

published in Dutton, Marsha (ed.), Aelred

of Rievaulx: The Historical Works, Cistercian Publications, 2005

Herman the Archdeacon, The Miracles of St

Edmund, translated by Tom Licence, Clarendon Press, 2014

Jacobus de Voragine, Legenda Aurea,

translated by William Granger Ryan, Princeton University Press, 2012

Jocelin of Brakelond, Chronicle of the

Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, translated by Diana Greenway and Jane Sayers,

Oxford World Classics, 2008

Langland, William, The Vision of Piers

Plowman, translated by Schmidt, Everyman, 1995

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2B-%2Bfrom%2Bwikimedia.jpg)