Today I have been teaching a class on popular - or lay - cult of saints, looking at various texts that unlike the grand Latin hagiographies were available to the common populace, not just because they were written in the vernacular, but also because they were performed in public. The emphasis of the lecture was on two types of texts. First we looked at a Corpus Christi play on Mary Magdalen, and it turned into a very enjoyable discussion on the relation of mystery plays with Ancient Greek and Roman theatre, following a question from one of my students, and this allowed me to point back to earlier lectures where I had talked about the transition from the Greek novel to early Christian hagiography. (I always feel a great pleasure when I'm able to connect the current lecture with earlier subjects.)

The second emphasis was on carols on saints, exemplified by a selection from Richard Leighton Greene's The Early English Carols (1977). Being in Middle English and interspersed with Latin quotations, the carols were difficult to grasp, and with the many uncertainties of the genre with regards to audience, authorship, purpose and rationale of form, we explored chiefly the carol as a form of hagiography conveying a condensed portrait of the saint's life and martyrdom, and how that life could be rendered very differently from one carol to the next.

To better illustrate this variation, we focussed on a selection of carols dedicated to St Stephen Protomartyr since his carols are numerous enough to allow for a relatively wide selection. In this blogpost I wish to present three of these carols, in which the martyrdom of St Stephen is narrated in rather different ways, showing the flexibility of the carol genre. The texts are taken from Greene's book, and in lieu of titles I use the numbering employed by Greene to differentiate between the carols.

97

Bodleian Library. MS. Douce 302

By John Audelay, 15th century

In reuerens of our Lord in heven,

Worchip this marter, swete Sent Steuen.

Saynt Steuen, the first matere,

He ched his blod in herth here;

For the loue of his Lord so dere

He sofird payn and passion.

He was stonyd with stons ful cruelle,

And sofird his payn ful pasiently:

'Lord of myn enmes thou Haue merce,

That wot not what thai done.'

He beheld into heuen on he

And se Jhesu stonde in his majeste

And sayd, 'My soule, Lord, take to the,

And foreyif myn enmys euerechon.'

Then, when that word he had sayd,

God thereof was wel apays;

His hede mekele to sleep he layd;

His sowle was takyn to heuen anon.

Swete Saynt Steuen, for vs thou pray

To that Lord that best may,

Whan our soule schal wynd away,

He grawnt us al remyssion.

Martyrdom - or lapidation - of Stephen

Yates Thompson 49, La légende dorée, Jacobus de Voragine, France, c.1470

Courtesy of British Library

98

Trinity College, Cambridge. MS. O. 3. 58

Fifteenth century

Eyam martir Stephane,

Prey for vs, we prey to the.

Of this marter make we mende,

Qui triumphauit hodie

And to heuene blysse gan wende

Dono celestis gracie.

Stonyd he was wyth stonys grete

Feruore gentis impie;

Than he say Cryst sitte in sete,

Innixum Patris dextere.

Thov preydyst Cryst for thinenmyse,

O martir inuictissime;

Thou prey for vs that hye Justyse

Vt nos purget a crimine.

Amen

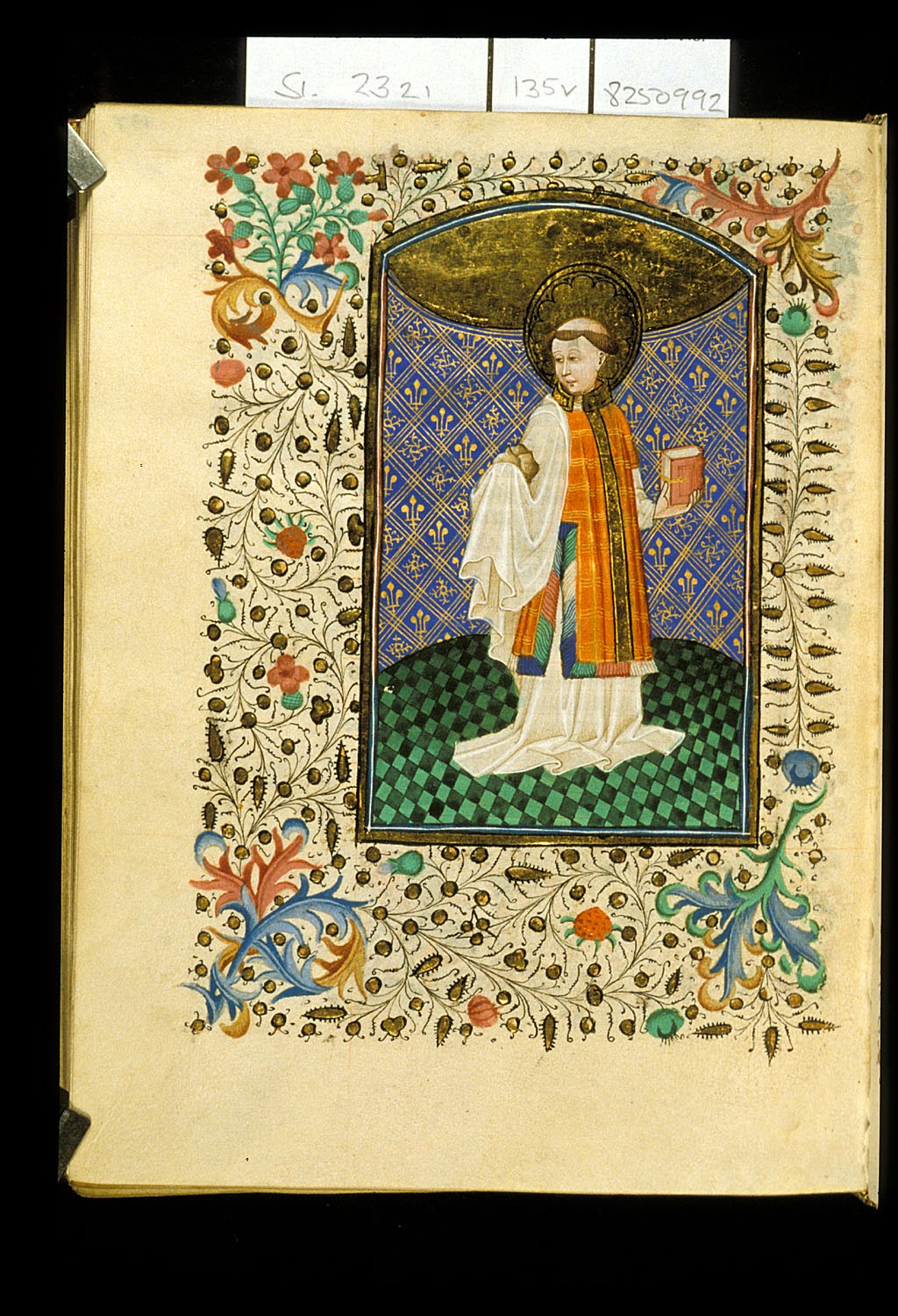

Stephen with his instruments of passion

Sloane 2321, English Book of Hours, use of Sarum, c.1440

Courtesy of British Library

Sloane 2321, English Book of Hours, use of Sarum, c.1440

Courtesy of British Library

100

Balliol College, Oxford. MS. 354

Sixteenth century

Nowe syng we both all and sum,

'Lapidauerunt Stephanum.'

Whan Seynt Stevyn was at Jeruzalem,

Godes lawes he loved to lerne,

That made the Jewes to cry so clere and clen,

'Lapidaverunt Stephanum.'

The Jewes, that were both false and fell,

Agaynst Seynt Stephyn they were cruell;

Hym to sle they made gret yell

Et lapidaverunt Stephanum.

They pullid hym without the town

And than he mekely kneled Down

Withle hte Jewes crakkyd his Crown,

Quia lapidavverunt Stephanum.

Gret stones and bones at hym they caste,

Veynes and bones of hym they braste,

And they kylled hym at the laste,

Quia lapidaverunt Stephanum.

Pray we all that now be here

Vnto Seynt Stephyn, that marter clere,

To save vs all from the fendes fere.

Lapidaverunt Stephanum.

These carols are interesting texts to research when looking at how the stories about saints are treated in different literary categories, and how the stories are rendered at different times in history. The three carols selected here are particularly fascinating in the difference between the first two, and the third. In the first two carols the narrative is focussed on Stephen and his martyrial triumph, and also his role as an intermediary, a point particularly clear in the first carol where Stephen prays for his enemies and is then exhorted by the singers of the carol. The third and latest carol, however, focusses rather gratuitously and viscerally on the martyrdom itself, the manner of Stephen's death and - with urgent insistence - on the guilt of the Jews in this enterprise. This is an interesting difference, but one from which it is difficult to extract much meaning as these carols are just snippets from a vast textual and cultural history, of which we know little of their immediate context of composition and who share only a subject matter and are not themselves textually related, at least not to our knowledge.

As the carols are presented in Greene's wonderful tome, it is also easy to fall prey to certain temptations in the attempted extraction of significance. Since these carols are numerically close together, thematically linked and follow a chronological trajectory where the last, most brutal of these selected here appear as an end-point, it's tempting to see that as an explanation of the increasingly vivid role of the Jews, who are more clearly represented in the second than in the first carol. This is of course tempting suggestion that caters to our taste for clear progression or regression in events, be they cultural, biological or psychological, but to follow such a thread would be to treat Greene's organisation of the carols as the original document rather than the result of an avid historian of carol and his attempt to handle an unwieldy mass of texts. I mention this as an apropos of how easy it is to give in to the urge towards orderly and simple transmissions of textual material, which is a methodological cul-de-sac for any historian of texts.

Ingen kommentarer:

Legg inn en kommentar